Chayei Sarah opens with the passing of Sarah Imeinu, whose life of faith leaves a legacy of devotion. Avraham purchases the Cave of Machpelah in Chevron—both a resting place for his beloved and the first eternal claim to the Promised Land. Seeking continuity, Avraham sends his servant to Aram to find a wife for Yitzchak. Through providence and prayer, Rivkah emerges—kind, decisive, and guided by Divine purpose. Their meeting fulfills the promise of the next generation. The parsha closes with Avraham’s final years: he remarries, blesses Yitzchak as his heir, and is laid to rest beside Sarah—his life complete, his covenant enduring.

#551 – Not to delay burial overnight — Deuteronomy 21:23

In Chayei Sarah: Avraham hastens Sarah’s kevurah, arranging purchase and interment without deferment.

Narrative roots: Genesis 23:2–4, 17–20.

#587 – Mourn for relatives — Leviticus 10:19

In Chayei Sarah: “To eulogize Sarah and to weep for her” — public aveilut and kavod ha-met.

Narrative roots: Genesis 23:2.

#499 – Buy and sell according to Torah law — Leviticus 25:14

In Chayei Sarah: Avraham executes a fully witnessed, recorded transfer of field and cave “in the presence of the people,” establishing incontestable title.

Narrative roots: Genesis 23:10–13, 16–20.

#469 – Each individual must ensure that his scales and weights are accurate — Leviticus 19:36

In Chayei Sarah: Payment is “four hundred shekels of silver, over la-socher” — merchant-standard weight; exemplary honesty.

Narrative roots: Genesis 23:16.

#214 – To fulfill what was uttered and to do what was avowed — Deuteronomy 23:24

In Chayei Sarah: Eliezer swears and then faithfully performs the mission to secure a wife for Yitzchak exactly as pledged to Avraham.

Narrative roots: Genesis 24:2–9, 42–48.

#209 – Not to swear falsely in G-d’s Name — Leviticus 19:12

In Chayei Sarah: The servant invokes Hashem in oath and testimony with integrity — truthfulness under the Divine Name.

Narrative roots: Genesis 24:3, 37–41.

#122 – To marry a wife by the means prescribed in the Torah (kiddushin) — Deuteronomy 24:1

In Chayei Sarah: The shidduch culminates, “Yitzchak brought her into his mother Sarah’s tent… and he married Rivkah.”

Narrative roots: Genesis 24:64–67.

#162 – Not to marry non-Jews — Deuteronomy 7:3

In Chayei Sarah: Avraham adjures that a wife not be taken from the Canaanites; the match must come from his family to join the covenant.

Narrative roots: Genesis 24:3–4.

#125 – To have children with one’s wife — Genesis 1:28

In Chayei Sarah: The entire mission seeks the covenant’s next generation through Yitzchak and Rivkah; the family blesses, “May you become thousands of myriads.”

Narrative roots: Genesis 24:7, 60, 67.

#77 – To serve the Almighty with prayer daily — Exodus 23:25

In Chayei Sarah: “Yitzchak went out to pray in the field toward evening” — classic scene for regular avodah through tefillah.

Narrative roots: Genesis 24:63.

#550 – Bury the executed [as well as all deceased] on the day they are killed — Deuteronomy 21:23

In Chayei Sarah: The parsha ends with Avraham’s burial by Yitzchak and Yishmael — prompt, dignified interment for the deceased.

Narrative roots: Genesis 25:8–10.

Rashi highlights that Sarah’s years were “all equally good” and that the tripartite count (“100, 20, 7”) teaches moral and aesthetic perfection across her life (23:1, שני חיי שרה). Her passing is placed immediately after the Akeidah: the report that Yitzchak had been readied for sacrifice shocked her soul, and she died (23:2, לספוד לשרה ולבכותה).

At Kiryat Arba, Rashi offers two etymologies—four giants or four couples to be buried there (Adam–Chavah, Avraham–Sarah, Yitzchak–Rivkah, Yaakov–Leah) (23:2, בקרית ארבע). Avraham’s negotiations are public and precise: he approaches as “גר ותושב”—stranger and settler, signaling both humility and legal standing (23:4); he insists on “בכסף מלא” (full value) (23:9); and Rashi notes Ephron’s duplicity (his name written defectively when he takes heavy “centenarii” coins) (23:16). The deed is secured “before all who entered the gate” and thus rises in stature—from a commoner to a king (23:17–18; 23:10, 23:18). Covenant becomes concrete through law, witnesses, and payment.

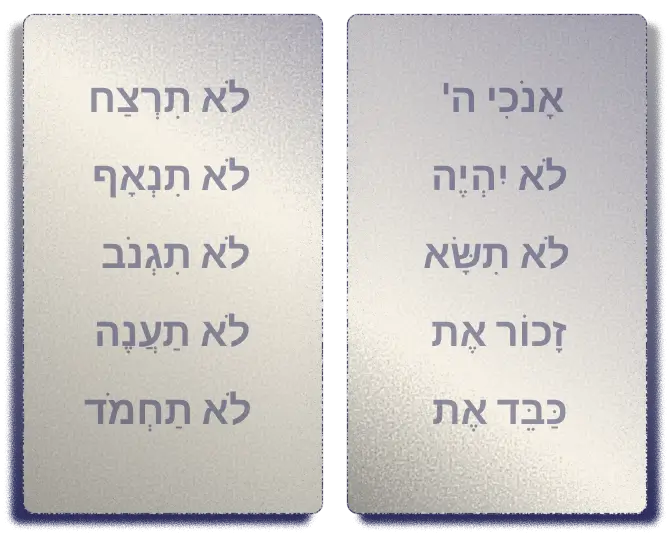

Turning to Eliezer’s mission, Rashi frames the oath “תחת ירכי” as swearing on a mitzvah-object—brit milah—the first command given to Avraham (24:2). Avraham’s language “ה’ אלקי השמים” contrasts past and present: once G-d was known only in the heavens; through Avraham’s proclamation He is now known on earth (24:7). At the well, the sign Eliezer requests discerns chesed—“אתה הוכחת”—fitness for Avraham’s house (24:14). Providential hints abound: waters rise toward Rivkah (24:17), and the jewels symbolize national destiny (a בֶּקַע for half-shekel; שני צמידים for the two tablets; ten for the Aseret HaDibrot) (24:22). Rashi notes Eliezer’s order reversal when retelling events—to avoid being trapped by his words (24:47), and the “קפיצת הדרך”—miraculous shortening of the road (24:42). Around the home, Rashi colors the scene: Lavan runs when he sees the gold (24:29), and the house is cleared of idols before hosting (24:31). Crucially, Rivkah’s consent is sought—“ונשאלה את פיה” (24:57), and her kin bless her: “היי לאלפי רבבה” (24:60).

Yitzchak, returning from Be’er Lachai-Roi—to bring Hagar back for Avraham—goes out to pray (“לשוח” as tefillah) at eventide (24:62–63). When Rivkah arrives, she veils herself (24:65), and Yitzchak brings her into Sarah’s tent; Rashi records the three miracles that returned with Rivkah—the Shabbat-to-Shabbat lamp, blessing in the dough, and the protective cloud (24:67).

Finally, Rashi identifies Keturah as Hagar, her deeds now “fragrant like incense” (25:1). Avraham’s gifts to the sons of the concubines (transmitted “names of impurity,” or—alternatively—all gifts he had received because of Sarah) distance them while the inheritance goes to Yitzchak (25:5-6). Yishmael’s repentance appears in his yielding precedence to Yitzchak at the burial (25:9), and Hashem Himself blesses Yitzchak after Avraham’s death (25:11).

📖 Rashi References (Chayei Sarah):

23:1–2; 23:4; 23:9–10,16–18; 24:1–2,7,14,17,22,29,31–33,36,42,47,57–60,62–67; 25:1,5–6,9,11.

“Hashem blessed Avraham in all things” (Bereishit 24:1).

For the Rambam, this verse signifies not material prosperity but intellectual-spiritual harmony — bakol meaning a life fully ordered toward the Divine. In Moreh Nevukhim III:51, he teaches that true blessing is the perfection of daʿat Elohim—knowledge of God expressed in right conduct. In Hilchot Deʿot 1:4, moral balance becomes the outflow of intellect sanctified by wisdom.

Avraham’s “blessing in all” thus marks a completed integration of thought, feeling, and action — the soul at peace through alignment with Divine order.

Sources:

When Avraham purchases the cave of Machpelah (Bereishit 23), the Rambam sees ethics wedded to intellect: transparent negotiation, public consent, and full payment represent the moral law in civic life. In his view of hashgachah pratit, Providence cleaves to those who act rationally and justly. The righteous secure not only faith but moral order within society.

Avraham’s dignity in mourning and precision in transaction embody the via media of Aristotelian virtue: emotion governed by wisdom, compassion bounded by law.

Sources:

When Avraham makes his servant swear “under his thigh” (Bereishit 24:2), Rambam interprets the gesture not mystically but as covenantal realism: grounding sacred oaths in a tangible mitzvah-object. In Hilchot Avodah Zarah 1:3, he defines idolatry’s root as intellectual error — the failure to connect reverence to reason.

Avraham’s instruction that Yitzchak not marry a Canaanite rests on prudence, not prejudice: moral alignment ensures spiritual continuity. Here sekhel hamaʿaseh (practical reason) replaces blind custom; obedience becomes intelligent devotion.

Sources:

Eliezer’s prayer at the well (Bereishit 24:12–14) exemplifies Rambam’s doctrine that Divine assistance responds to perfected intellect and moral disposition. Providence operates through the alignment of reason and goodness, not arbitrary miracle.

Rivkah’s spontaneous kindness reveals the same ethical symmetry Rambam attributes to prophetic fitness: right action flowing from stable character. “The righteous,” he writes (Guide III:18), “are guided by the light of their intellect, and the light of the intellect is God Himself.”

Sources:

The betrothal of Yitzchak and Rivkah is, for Rambam, the triumph of moral discernment over passion. Marriage symbolizes the harmonization of body and soul, where reason governs affection. In Hilchot Ishut 15:19*, he links holiness in union to measured desire guided by wisdom — “Sanctify yourself in what is permitted.”

Thus the covenant of love mirrors the covenant of intellect: faithfulness becomes the rational extension of moral self-command.

Sources:

“Yitzchak went out to meditate in the field toward evening” (Bereishit 24:63). Rambam reads this as the paradigm of tefillah seichelit — contemplative prayer that unites cognition and devotion. In Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah 7:1–2, prophecy arises when imagination and intellect are purified through habitual reflection.

Yitzchak’s afternoon prayer is not ecstatic impulse but sustained awareness: contemplation flowering into moral calm — the intellect turning upward through gratitude.

Sources:

Avraham’s reunion with Keturah (Bereishit 25:1) reveals the perfected harmony of desire under intellect. In Hilchot Deʿot 1:2–3*, Rambam defines holiness as disciplined balance — neither repression nor indulgence. The “gifts” to concubines symbolize the relegation of lower drives, while the full inheritance through Yitzchak represents the soul’s true lineage of wisdom.

The righteous die “satiated with days” — a philosophical peace: when every faculty finds completion in reasoned order.

Sources:

After Avraham’s death, “Hashem blessed Yitzchak his son” (Bereishit 25:11). For Rambam this signifies the transmission of hashgachah through moral continuity: knowledge of God begets providence for the next generation. As intellect perfects virtue, Divine blessing becomes an enduring law of moral causation.

Sources:

In Chayei Sarah, Rambam’s Avraham achieves the synthesis of his philosophy:

knowledge transformed into justice, faith expressed through rational love, and Providence revealed in ethical order.

Every act — burial, oath, marriage, prayer — becomes a meditation on wisdom embodied. The intellect’s perfection is not withdrawal from the world but the sanctification of the world through understanding.

For the Ralbag, Chayei Sarah portrays how hashgachah pratit (personal Providence) cleaves to those who perfect their deeds and understanding. Avraham’s conduct—dignified mourning, prudent acquisition of a burial plot, and rational planning for Yitzchak’s marriage—models a life where reason directs virtue and thereby merits Divine favor.

Burial & Civic Ethics (Gen. 23). Avraham’s purchase of Me’arat HaMachpelah showcases scrupulous honesty, public consent, and respect for neighbors; Providence grants him honor as a “nasí Elokim” among the Hittites (23:6). Ralbag notes Ephron’s tactics and Avraham’s insistence on full-weight, clean silver and a witnessed transfer—ethics that dignify both the living and the dead.

Ralbag on Torah, Genesis 23

Marriage Strategy & Prudence (Gen. 24). Avraham forbids a Canaanite match not out of xenophobia but out of moral-intellectual fitness for the covenant. Eliezer’s test seeks a woman whose generosity is spontaneous and energetic—evidence of stable virtue fit for the house of Avraham. Providence aids human planning; Eliezer’s prayer, thanksgiving, and urgency align with disciplined action.

Providence After Avraham (Gen. 24). Avraham distributes gifts and distance to prevent strife; he dies “old and satisfied,” and G-d’s blessing continues with Yitzchak—signs that the righteous are watched over to the end of their days. Ralbag also underscores the endurance of the acquired intellect after death.

Ralbag on Torah, Genesis 24

Summary of Ralbag’s To’alot in Chayei Sarah

📖 Sources

Chayei Sarah — The parsha opens with loss and continuity: Sarah’s passing, Avraham’s mourning, and the search for a bride for Yitzchak. The Chassidic masters read this not as an ending but as the soul’s transformation from life below to influence above — the revelation of holiness within human constancy and devotion.

The Baal Shem Tov interprets Avraham’s purchase of Me’arat HaMachpelah as a symbol of the soul’s double dwelling — physical and spiritual. Just as the cave held layers within layers, so too the righteous person transforms worldly acts into resting places for the Divine. When Avraham insists on paying full price, he teaches that sanctity requires avodah be’emet — honest effort that refines material life into holiness.

The Kedushat Levi (R. Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev) explains that Avraham’s blessing “bakol — in all things” reflects inner completion: when one’s love, deeds, and thoughts align with G-d’s will, nothing is lacking. True blessing, says the Kedushat Levi, is not abundance but wholeness — to see the Divine in every circumstance, even in loss.

The Sfas Emes (Chayei Sarah 5631) sees Eliezer’s mission as the journey of the soul seeking divine connection in the world. Eliezer’s test at the well represents the awakening of hidden kindness (chesed nistar) — the moment when faith translates into spontaneous generosity. Rivkah’s immediate response shows how emunah becomes action, revealing that every encounter is an opportunity for revelation through love and service.

In Chayei Sarah, the Chassidic path is drawn between earth and heaven — mourning becomes gratitude, labor becomes faith, and the ordinary becomes eternal. Holiness endures not through visions above but through steadfast devotion, compassion, and integrity below.

📖 Sources

Rabbi Sacks taught that Chayei Sarah is not a story of death, but of faith’s endurance through continuity. Even after Sarah’s passing, Avraham’s every act — securing a burial site, sending his servant to find a wife for Yitzchak — affirms that faith is not a moment of inspiration but a lifelong commitment to build a future shaped by G-d’s promise.

Avraham’s purchase of Me’arat HaMachpelah reveals his belief that holiness must be made concrete — a field, a cave, a home — where memory and hope dwell together. His insistence on paying full price, Rabbi Sacks explains, turns faith into responsibility: “To live the covenant is to translate belief into deeds, and ideals into institutions.”

In Yitzchak’s marriage to Rivkah, love itself becomes an act of covenantal faith. The story closes not in mourning but in renewal — the first Jewish love story grounded in shared mission and moral destiny.

“Faith is not what happens to us, but what we build in response to what happens.”

— Covenant & Conversation, Chayei Sarah 5771

Avraham’s final years show that love, faith, and action are never separate paths — they are the living inheritance of Chayei Sarah, where holiness takes root in ordinary acts of loyalty and devotion.

Seven Reflections on Faith, Education, and the Soul of Israel

Sarah’s greatness was her unbroken innocence — a purity that endured through trial, exile, and age. From her life, Rav Kook draws a philosophy of chinuch (education): the soul’s sanctity must be protected, not manufactured. Childhood is not merely a stage to be outgrown but the wellspring of holiness itself — “Do not harm My anointed ones — these are the schoolchildren” (Shabbat 119b). Education must therefore preserve the divine laughter of Yitzchak, nurturing souls that retain wonder amid a world of cynicism.

Abraham’s wisdom was universal; Sarah’s sanctity was particular. Rav Kook distinguishes their callings: Avraham spread faith through reason and philosophy, Sarah through deed and holiness. Her Torah shel Ma’aseh — the Torah of action — grounds universal ideals in the living reality of a nation devoted to mitzvot. Thus Sarah remains both “the princess of her people” and “princess of the world”: embodying how Jewish particularism refines humanity’s moral soul.

The Torah’s detailed account of Sarah’s burial in Hebron marks the first Jewish claim to the Land. Rav Kook teaches that Hebron represents havdalah — sacred distinction. Just as Sarah demanded that Yishmael be separated from Yitzchak, so too her burial inaugurates the separation of the Land of Israel for holiness. Hebron becomes the root of Jewish sovereignty: David’s first kingdom, the foundation for Israel’s future sanctity. In Sarah’s resting place, Rav Kook sees the birth of the covenant between people, land, and destiny.

The Machpelah is “doubled” because it unites two paths of elevation — human intellect and divine revelation. Adam and Chavah embody the ascent through reason; the Patriarchs and Matriarchs, the ascent through Torah. For Rav Kook, the double cave symbolizes integration: body refined through burial, soul through Torah. True holiness arises when wisdom and faith, nature and revelation, harmonize — when intellect bows not in defeat but in partnership with the Divine.

“Yitzchak went out to meditate (lasuach) in the field” — a verse that joins speech and growth. Prayer, Rav Kook writes, is the soul’s natural flowering: “The soul is always praying, seeking to fly to its Beloved.” The afternoon, when labor softens into reflection, invites this inner blooming. Lasuach also means “to plant” — suggesting that through prayer, the soul roots heaven into earth, cultivating divine vitality amid the ordinary field of life.

In 1929, when the Hebron community was massacred, Rav Kook’s grief became prophecy. At the memorial he declared: “The holy martyrs of Hebron need no memorial; we must remember what Hebron means to us.” He invoked Caleb’s defiant faith — “We shall surely go up!” — affirming that Eternal Israel never falters. Hebron, the city of the Patriarchs, must not be mourned but rebuilt; its stones are living witnesses to the indestructible bond between Israel, its land, and its God.

Why so many verses about Eliezer’s conversation? Because the “speech of the Patriarchs’ servants” reveals a Torah that flows naturally from sanctified life. The Avot embodied a Torah of authenticity — holiness lived, not legislated. In exile, Judaism became the Torah of detail and discipline; in redemption, it must recover the Torah of life, radiant and creative. The task of our age, Rav Kook says, is to unite both Torahs — halachic precision with inner light — revealing a faith of grandeur, beauty, and national rebirth.

Across these teachings, Rav Kook traces a single current: from Sarah’s purity to Isaac’s prayer, from Hebron’s burial cave to the Torah of redemption. Chayei Sarah becomes a map of spiritual continuity — the merging of innocence, courage, intellect, and holiness into one seamless covenant. Through the laughter of faith and the courage of rebuilding, the soul of Israel learns again to live with childlike wonder and prophetic strength, rooted deeply in its land yet open to the light of all humanity.

📖 Sources

“And Avraham came to eulogize Sarah and to weep for her.”

(Bereishit 23:2)

Every soul must learn to live its own Chayei Sarah — to sanctify loss through continuity, to translate holiness into life that endures. The parsha opens in mourning yet flows immediately into motion: purchase, oath, journey, marriage. In Chayei Sarah, faith becomes tangible — written into land, law, covenant, and compassion.

Avraham’s conduct at Chevron models moral clarity in the public square. As Rashi and the Ralbag note, he insists on full payment “בכסף מלא” and open witness, turning grief into integrity. Ramban explains that this legal precision roots faith in the soil of Eretz Yisrael — the first concrete fulfillment of the promise “to your seed I will give this land.” Civic ethics and covenantal destiny fuse: honesty itself becomes an act of holiness.

Rambam reads “Hashem blessed Avraham bakol” as the perfection of the moral intellect: every faculty aligned toward G-d. Avraham’s knowledge of the Divine overflows into action — the wisdom to plan, choose, and act justly. In Chayei Sarah, Providence does not replace human effort; it dwells within disciplined reason.

Eliezer’s mission reveals the measure of chesed that defines Avraham’s house. At the well, Rivkah’s swift generosity — “drink, and I will draw for your camels also” — transforms ordinary kindness into covenantal revelation. The Sfas Emes calls this chesed nistar, hidden kindness made visible through instinctive goodness. For the Kedushat Levi, such love is true bakol — wholeness that sees G-d in every circumstance.

Yitzchak’s lasuach basadeh at evening becomes, in Rav Kook’s vision, the flowering of the soul. Prayer is not escape but cultivation; the spirit, like a tree, draws nourishment from effort and time. Through quiet meditation, the finite body joins the infinite pulse of life.

Sarah’s tent, rekindled by Rivkah, reminds us that holiness is not invented but restored — the lamp relit, the dough blessed, the cloud returned. The Baal Shem Tov teaches that the double cave of Machpelah mirrors this union of worlds: physical and spiritual, intellect and Torah, the human mind and the Divine will.

And from Hebron, faith continues to echo. Rav Kook’s cry after the 1929 massacre — “We will not abandon the city of our fathers” — transforms mourning into courage. Like Avraham’s insistence to secure the cave, his words root the eternal bond between Am Yisrael and its land: to build again in honor and in holiness.

So today, Chayei Sarah calls each of us:

When we honor the past through ethical life and loving continuity — when wisdom, humility, and hope dwell together — we too become heirs to Sarah’s laughter and Avraham’s faith made enduring.

📖 Supporting Sources

Rashi reads the triple count (“100 years, 20 years, 7 years”) as three perfect stages: at 100 she was as free of sin as at 20; at 20 as beautiful as 7. “The years of Sarah’s life” teaches that all her years were equally good. The parsha begins immediately after the Akeidah: Sarah’s soul departed when she heard Yitzchak had been readied for sacrifice.

📖 Sources:

“Kiryat Arba” refers either to the four giants who lived there or the four patriarchal couples buried there (Adam–Chavah, Avraham–Sarah, Yitzchak–Rivkah, Yaakov–Leah). “Machpelah” means “double,” a cave with two levels or paired burials. Avraham insists on בכסף מלא — paying full value for holiness made real.

📖 Sources:

Avraham introduces himself as both stranger and resident — ready to purchase as a foreigner yet entitled by promise. His request for an אחוזת קבר permanent burial holding shows reverence for law and land.

📖 Sources:

Ephron, raised that day to negotiator, flatters Avraham but demands a steep price in “centenarii” coins. The Torah repeats the transfer “before all who entered the gate” to show a fully public, lawful deed. The field “rose” — its status elevated from commoner to kingly possession.

📖 Sources:

Bakol (“in all things”) equals the gematria of בן (son): since Avraham now had a son, his concern turned to finding him a wife. “Under my thigh” invokes a mitzvah-object — the sign of the covenant. Avraham calls G-d now “of Heaven and Earth,” for through him the Name became known on earth.

📖 Sources:

At the well Eliezer prays for a sign revealing innate kindness. The waters rise toward Rivkah — proof of Providence. Her gifts mirror Israel’s destiny: a בקע (half-shekel), two bracelets (two Tablets), ten gold shekels (the Aseret HaDibrot). Avraham’s faith flowers through acts of gracious initiative.

📖 Sources:

Lavan runs when he sees the gold and declares his house “cleared out” (from idols). Eliezer recounts his journey with precision, reversing order to avoid entrapment. Rivkah’s voice is sought: “ונשאלה את פיה” — ask the maiden herself. She answers simply, “אלך.” The family blesses her: “היי לאלפי רבבה… וירש זרעך שער שנאיו.”

📖 Sources:

Returning from Be’er Lachai-Roi (after bringing Hagar back for Avraham), Yitzchak goes out “lasuach basadeh” — to pray. Rivkah, seeing him, inclines herself from the camel and veils her face in modesty. Brought into Sarah’s tent, the three miracles return: the ever-burning lamp, the blessing in the dough, and the protective cloud.

📖 Sources:

“Keturah” is Hagar — her deeds now “fragrant like incense.” She remained chaste after parting from Avraham. “Concubines” (plural defective) implies one. His “gifts” to the sons of concubines are either mystical names or worldly presents sent eastward. At his death Ishmael yields precedence to Yitzchak — proof of repentance. Hashem then blesses Yitzchak.

📖 Sources:

Rashi’s parsha reveals holiness within earthly life: Avraham mourns and negotiates with integrity; Eliezer acts with faith and wisdom; Rivkah chooses with courage; Yitzchak prays with stillness. Covenant becomes concrete — a field, a tent, a home — where faith flowers through justice and kindness.

The structure “one hundred years, twenty years, seven years.” – 23:1

Ramban contests Rashi’s claim that the repeated “years” equates each span (100/20/7). He argues the repetition is normal Hebrew usage; the equating comes only from the closing phrase “the years of the life of Sarah,” which collectively includes and levels them—unlike by Avraham or Yishmael, where that catch-all is absent.

“And Avraham came” & where he came from. – 23:2

Ramban weighs two midrashic trajectories—Beer-Sheva vs. Har HaMoriah—and reconciles them: the command of the Akedah likely reached Avraham in Beer-Sheva; after the Akedah he went there to thank G-d, learned of Sarah’s death, and then came to Chevron. He also offers a peshat that “came” can mean “set himself to” the eulogy, without implying intercity travel.

Ger v’toshav; Ephron and the purchase. – 23:4-15

Avraham identifies as both “stranger and resident,” asking for a permanent family plot; the Hittites’ reply treats him as a prince. Ramban explains Avraham’s indirect approach to Ephron (social protocol), the language of “give” in sales idiom (“that he may give me” = sell but as a gift in posture), and rejects “Machpelah” as a topological “double cave” etymology, treating “Machpelah” as a place-name. Ephron broadens the deal from “cave” to “field + cave,” whether out of etiquette or strategy; Avraham then pays a full, public, merchant-rate price.

Why the narrative re-specifies place and land. – 23:19

The text redundantly anchors the site (field, cave, before Mamre, which is Chevron, in Canaan) to underscore that Sarah died and was buried in Eretz Yisrael; it also records G-d’s kindness—Avraham’s reputation (“nasi Elokim”) and the fulfillment of “I will make your name great”—and fixes the patriarchal burial place for posterity’s honor.

Why the oath now. – 24:1

“Avraham was old” explains the urgency to bind the steward by oath: Avraham feared he might die before the mission’s completion; the steward governed the estate and Isaac would heed him. “Blessed … bakol” includes every human good; Ramban also preserves the deep derash that bakol hints to the attribute Kol and its emanation “bat” (Knesset Yisrael), indicating Avraham’s blessing in heaven and earth.

“Elokei ha-aretz/Elokei ha-shamayim,” country and kindred. – 24:3-8

“G-d of the land” fits Eretz Yisrael’s special Divine relationship; “of the heavens” alone is said regarding Avraham’s earlier life outside the Land. “To my country and birthplace” refers to Mesopotamia (Haran)—Ramban rejects sending to Ur Kasdim or any Hamitic lines. If the family refuses, the steward is released from that clause (going there), but never from the ban on Canaanite marriages.

The steward’s conduct and signs. – 24:10-32

“All his master’s goods in his hand” is best read as “of his master’s goods” (he took a representative bounty, as in “ten donkeys laden with the good of Egypt”). His test (“give me to drink—and also the camels”) requests that G-d appoint the fitting bride; her generous action confirms fitness and family. Midrashic notes: waters rising for Rivkah the first time (hence “she filled … and came up”) and Lavan, not the steward, actually ungirding the camels and drawing water for guests.

Meeting Isaac; modesty and tent of Sarah. – 24:61-67

“Rivkah arose … and followed the man”—Ramban reads the steward’s vigilance to guard her on the way. “Vatipol min ha-gamal” = she inclined herself modestly on the camel (not a literal fall) upon seeing a dignified figure, then veiled. “And Isaac brought her into his mother Sarah’s tent” records continuity of Sarah’s sanctity (Onkelos: she was like Sarah), the reason for “and he loved her” and for Isaac’s comfort after his mother.

Keturah and “concubines.” – 25:3-6

By peshat, since “through Isaac shall seed be called,” other unions are classed as “concubines” relative to inheritance, even if a woman (e.g., Keturah) was taken as a formal wife; Scripture truncates her lineage—likely Canaanite—because the covenantal line is only through Isaac. (Ramban also notes the halakhic nuance: “concubine” in Tanakh = without erusin, not merely lacking a rabbinic ketubah.)

“Old and satisfied,” Ishmael’s end. – 25:8-17

“Old and full of years” marks righteous fullness—desires sated, no craving for “more days.” Ramban underscores that “expired (vayigva) and was gathered” is a righteous death without prolonged suffering; Scripture records Yishmael’s years because he repented, so his passing is narrated like the righteous.

📖 Ramban References (Chayei Sarah):

23:1, 23:2, 23:4-15, 23:19, 24:1, 24:3-8, 24:10-32, 24:61-67, 25:3-6, 25:8-17.

In Sforno’s commentary on Parshas Chayei Sarah, the narrative of transition—from Sarah’s passing to the establishment of Rivkah as her spiritual successor—unfolds as a study in covenantal continuity, moral conduct, and reverence for both life and death. Sarah dies only after a worthy successor has been born and Avraham is informed, illustrating divine timing and kavod ha-met, the honor due to the deceased (23:2). Before the burial, Avraham’s actions toward the Hittites show that the technical status of avelut had not yet begun, allowing him to arrange the acquisition of a family burial site (23:3). His declaration “ger v’toshav” reveals both humility and intent to settle in the land, while his insistence on purchasing the Ma’arat HaMachpelah for full price “b’mivchar kvareinu kevor” ensures a permanent and public claim, beyond reproach or later contest (23:4–20). This act of lawful acquisition anchors the covenant materially in the land of Canaan and reflects Avraham’s scrupulous integrity before G-d and man.

As Avraham turns to securing a wife for Yitzchak, Sforno highlights his faith in divine providence and the moral rigor guiding human agency. Aware of his wealth and advanced age, Avraham charges his servant Eliezer under oath to avoid Canaanite alliances and to trust that “G-d, the G-d of Heaven, will send His angel” (Elokei haShamayim yishlach mal’acho) to guide the mission (24:3–7). Eliezer’s prayer at the well is not divination but tefillah—a plea that G-d reveal the destined bride through an act of chesed and zerizut. Rivkah’s immediate response, her modesty, generosity, and alacrity, confirm that “You have instructed her to be worthy of Yitzchak” (24:14–21). Her family’s submission—“We cannot speak evil or good… take and go as G-d has spoken” (24:49–51)—embodies chesed ve’emet, yielding personal preference to divine decree. When asked if she will go immediately, Rivkah’s ready assent and the blessing she receives—“Our sister, be for thousands of myriads, and may your seed inherit the gates of their enemies” (24:60)—mark her as the vessel through whom Avraham’s covenantal promise continues.

The parsha concludes with Yitzchak’s contemplative prayer at eventide, his reverent meeting with Rivkah—who veils herself in awe—and their union, which brings him comfort after Sarah’s death (24:62–67). Avraham’s later years, described with serenity and foresight, include his equitable distribution of gifts during life to avoid strife and his peaceful passing “satisfied and gathered to his people,” a phrase denoting the eternal life of the righteous (25:6–8). Across these episodes, Sforno’s commentary weaves a moral and theological arc: the sanctity of burial, the ethics of acquisition, the providence guiding human vows, and the fusion of tefillah and tzni’ut in the founding of the next generation. Through transparency, humility, and faith in G-d’s guidance, the covenant of Avraham becomes concrete—rooted in the land, embodied in family, and sealed in legacy.

Abarbanel’s analysis of Parshas Chayei Sarah frames the unit (Gen 23:1–25:1) around a battery of methodological “questions” that illuminate law, theology, and narrative craft. On Sarah’s lifespan formulation and the phrase “shnei chayei Sarah,” he argues the Torah marks distinct phases—vigor, old age, and deep senescence—each counted as authentic “life,” hence the doubled formula (Gen 23:1). Sarah’s death at Chevron, while Avraham was in Be’er Sheva, reflects deliberate family logistics—securing residence in Eretz Canaan and, by received tradition, the Machpelah burial of Adam and Chavah—prompting Avraham’s urgent journey to eulogize and bury (Gen 23:2). The public purchase is juridically meticulous: Avraham addresses the Hittites to force an open, inalienable conveyance; Ephron’s ostentatious “gift” is converted into a full-price sale; the silver is verified by a city expert (“over to the merchant,” i.e., negotiable currency examined), and the title is perfected first by payment and deed (“vayakam hasadeh”) and then by chazakah through burial (Gen 23:3–20). Abarbanel justifies special burial on physical, spiritual, and kavod grounds, and on separation from Canaanite practices, hence the insistence on Machpelah in the sanctity of the Land (Gen 23:4–20). Turning to Yitzchak’s shidduch, Avraham’s oath “under the thigh” recalls brit milah and swears by “the G-d of heaven and earth,” while excluding Canaanite wives for reasons of cursed lineage and transmissible moral dispositional traits; Eliezer’s well “test” is not nichush but prayerful selection for chesed, zerizut, and tzniut that Rivkah demonstrably embodies (Gen 24:1–27). Eliezer’s retelling strategically adapts details to persuade Lavan and Betuel, who concede, “From G-d has this matter issued,” leading to Rivkah’s immediate assent and blessing (Gen 24:28–61). Finally, Abarbanel explains Avraham’s later marriage to Keturah as providential—fulfilling “father of many nations,” humbling Yishmael’s claims, and demonstrating that only Yitzchak inherits the covenant—while his typology of “vayigva, vayamat, vayei’asef el amav” distinguishes bodily decline, composite death, and the soul’s gathering, thereby articulating a comprehensive orthodox-academic theology of mortality and legacy (Gen 24:62–67; 25:1–11).

Overview

Across four essays from Toras Avigdor on Parshas Chayei Sarah, a coherent theology emerges: the Jewish home as prototype Mikdash; extremism-in-service (meshuga ish haruach) as the engine of covenantal greatness; intercessory prayer for others as a binding duty that must be paired with concrete action; and a sobering doctrine of historical “sifting,” wherein only the most loyal endure as the Am Hashem. Read together, these works outline an ethic of sanctified domestic life, audacious idealism, responsible agency paired with tefillah, and multi-generational fidelity.

Sarah’s tent constituted the earliest “sanctuary,” establishing the Jewish home as a locus for the Shechinah and the template for later sacred institutions.

Practical Program

Avraham’s refusal to intermarry with Malkitzedek’s admirable but “not-extreme-enough” community, and Eliezer’s test for Rivkah, model a standard of beyond-the-line avodat Hashem that others may scorn—but Heaven elects.

Practical Program

Avraham’s appeal to Bnei Cheis (פִּגְעוּ־לִי) encodes a dual strategy: act as a responsible agent, and pray as a duty—for others—in truth.

Practical Program

From Bereishit onward, history is narrated as divine sifting toward a people most loyal to Hashem; Avraham’s late-life separation from six sons exemplifies painful selection for maximal fidelity.

Pattern of Sifting

Contemporary Applications

Integrative Takeaways

Dive into mitzvos, tefillah, and Torah study—each section curated to help you learn, reflect, and live with intention. New insights are added regularly, creating an evolving space for spiritual growth.

Explore the 613 mitzvos and uncover the meaning behind each one. Discover practical ways to integrate them into your daily life with insights, sources, and guided reflection.

Learn the structure, depth, and spiritual intent behind Jewish prayer. Dive into morning blessings, Shema, Amidah, and more—with tools to enrich your daily connection.

Each week’s parsha offers timeless wisdom and modern relevance. Explore summaries, key themes, and mitzvah connections to deepen your understanding of the Torah cycle.