www.Mitzvah-Minute.com

Part I — Avraham the Beloved and the Mystery of Exile

The patriarch Avraham emerges in the Torah as the prototype of faith and ethical courage. Isaiah’s epithet is strikingly intimate: “Seed of Abraham My friend” (Isaiah 41:8). The Talmud, however, frames a disquieting problem at the heart of covenantal history. In Nedarim 32a we read:

“Abraham our Patriarch — why was he punished, and his children enslaved to Egypt for 210 years?”

At stake is not merely historical causation but the moral structure of the covenant. The Torah enshrines a principle of judicial non-transferability:

“Parents shall not be put to death for children, nor children be put to death for parents; each person shall die for his own sin.” (Deuteronomy 24:16)

The Prophets reaffirm the same rule:

“Only the person who sins shall die. A child shall not share the burden of a parent's guilt, nor shall a parent share the burden of a child's guilt.” (Ezekiel 18:20)

How, then, can exile be traced to the conduct of the patriarch?

The Three Talmudic Axes (Nedarim 32a)

The sugya articulates three distinct lenses through which Avraham’s greatness — and its consequences — are read:

1) Militarization of Disciples (Rabbi Abahu in the name of Rabbi Elazar).

The charge is that Avraham “made a draft [angarya] of Torah scholars,” grounding it in Genesis 14:14 — “He armed his trained men, those born in his household.” Here, even defensive, duty-bound warfare by Torah-devoted retainers carries spiritual costs at Avraham’s exalted level.

2) The Question at the Covenant (Shmuel).

During the Brit bein ha-Betarim, Avraham asks “בַּמָּה אֵדַע כִּי אִירָשֶׁנָּה” — “How shall I know that I shall inherit it?” (Genesis 15:8) and receives an answer of destiny: “Know well that your offspring shall be strangers…” (Genesis 15:13). The sugya reads this not as disbelief but as the infinitesimal hesitation unfitting for one at his spiritual altitude — an educative decree rather than retribution.

3) A Missed Moment of Kiddush Hashem (Rabbi Yochanan).

After victory over the four kings, Avraham’s refusal to appropriate spoils (vis-à-vis the king of Sodom) is noble restraint; yet the view here is that he might have leveraged the moment to sanctify the Divine Name publicly and draw rescued persons under the Abrahamic banner (Genesis 14:21–24).

The three approaches sketch a triangular field of leadership tension: action vs. faith, inquiry vs. trust, restraint vs. outreach. They do not denigrate Avraham; they magnify him by holding a tzaddik to standards of hair’s-breadth precision.

Consequence vs. Punishment: The Covenant’s Moral Grammar

Crucial to the classical conversation is the distinction between punitive guilt and covenantal consequence. The Torah’s bar on vicarious punishment stands; the Talmudic reading reframes the exile as pedagogy for a people forged to be a kingdom of priests. Three major mefarshim make that logic explicit:

- Ramban (on Genesis 15:13) views exile as the necessary crucible by which the chosen nation would be tempered for its vocation; the decree is covenantal formation rather than penal transfer.

- Maharal (Gevurot Hashem chs. 3–4) frames Avraham’s life as archetype (ma‘aseh avot siman le-banim): the events of the patriarchs reverberate as national templates, so that famine, descent to Egypt, covenantal trials, and deliverance are structural rather than accidental features of Israel’s history.

- R. Eliyahu Dessler (Michtav Me-Eliyahu, vol. I) explains exile as Divine equilibrium: an infinitesimal imperfection in faith at the summit becomes, across generations, the arena for its completion — faith converted from concept into history.

Thus the “why” in Nedarim 32a is not a calculus of blame but a theology of refinement: a tzaddik’s micro-deviation, measured at the altitude of intimacy with G-d, sets the stage for a people’s macro-correction.

“It Is Stormy Around Him”: Precision with the Righteous

The Mussar tradition makes this principle programmatic. In Mesilat Yesharim 4, Ramchal invokes the rabbinic maxim that the Holy One “scrutinizes judgment on His pious ones to the breadth of a hair” (Yevamot 121a). He then applies it to Avraham explicitly:

“Even so, he did not escape from judgment for slight words which he was not meticulous in, namely, for merely saying ‘with what will I know?’”

Ramchal’s point is not that Avraham’s faith faltered; rather, the nearer one stands to the Divine light, the narrower the tolerances become. What registers as negligible lower down is weighty at the summit. In that register, exile functions as education: the covenantal nation learns Avraham’s question by living its answer.

The same chapter cites a second illustration from Bereishit Rabbah 54 regarding Avraham’s covenant with Avimelech — a well-intended political act with long historical ripples. The Midrash’s rhetoric underscores the thesis: in a world governed by midat ha-din for the righteous, even “slight words” and prudent treaties carry teleological consequences.

Justice, Process, and the Integrity of Prophetic Ethics

Do these readings compromise the prophetic insistence that each soul bears only its own guilt? They need not — provided we maintain the category separation already implicit in Tanakh:

- Judicial culpability (the domain of Deuteronomy 24:16; Ezekiel 18:20) cannot be transferred.

- Covenantal formation, however, is inherited vocation: the children do not “pay” for the father’s sin; they become the field where the father’s unanswered questions are brought to completion.

Indeed, the Torah’s own narrative logic confirms this. The decree that Avraham’s seed will be strangers (Genesis 15:13) is accompanied by the promise of redemption (Genesis 15:14). The exile is embedded in a teleological arc whose end is Yetziat Mitzrayim, Sinai, and the birth of a Torah people.

Avraham’s Greatness Reframed

Seen through this lens, Nedarim 32a elevates Avraham rather than diminishes him. The sugya presumes his singular stature; it is precisely because he is אֹהֲבִי — “My friend” (Isaiah 41:8) — that his (hair’s-breadth) becomes the nation’s מַכָּה בַּפָּטִישׁ (final shaping blow). The exile is not Divine anger but Divine artistry. Avraham’s בַּמָּה אֵדַע becomes Israel’s יָדוֹעַ תֵּדַע — a knowledge inscribed not only in mind but in collective memory.

This frames the program of the series that follows. If Part I establishes the covenant’s moral grammar — consequence, not punishment — then Parts II–VI will trace how Ramchal turns that grammar into discipline: from Zehirut (vigilance) to Zerizut (alacrity), Nekiyut and Taharah (Cleanliness and Purity of Intention), Kedushah (holiness), and finally Ruach HaKodesh (inspiration). The question posed in Part I — How can a saint’s hair’s-breadth shape centuries? — receives its practical answer: by forming a people whose spiritual tolerances are trained to the same precision.

Sources (primary)

- Nedarim 32a — question and three views.

- Genesis 14:14; 14:21–24; 15:8; 15:13 — war of four kings; king of Sodom; covenant question and decree.

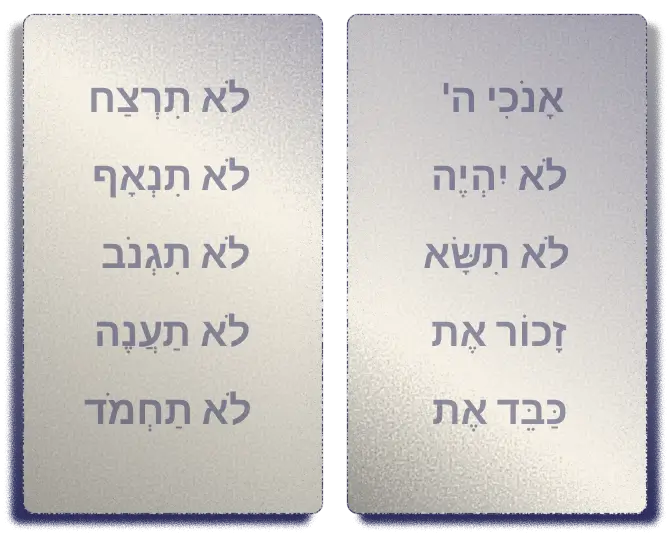

- Deuteronomy 24:16 — non-transferability of judicial guilt.

- Ezekiel 18:20 — each soul bears its own liability.

- Isaiah 41:8 — “Seed of Abraham My friend.”

- Yevamot 121a — scrutiny of the pious to a hair’s breadth.

- Mesilat Yesharim 4 — Ramchal on Avraham’s “did not escape from judgment.”

- Bereishit Rabbah 54 — Avimelech treaty and delayed rejoicing.

Sources (secondary / orientation)

- Ramban to Genesis 15:13 — exile as formative.

- Maharal, Gevurot Hashem chs. 3–4 — patriarchal archetype for national history.

- R. Eliyahu Dessler, Michtav Me-Eliyahu, vol. I — exile as Divine