Vayeitzei traces Yaakov’s departure from Be’er Sheva and his journey into exile. Stopping at the future site of the Mikdash, he experiences a revelatory dream in which G-d affirms the covenantal promises of protection, return, and national destiny. Arriving in the home of his uncle Lavan, Yaakov spends twenty demanding years tending Lavan’s flocks, navigating persistent deception while steadily prospering through divine favor. Within this complex household he marries Leah and Rachel and fathers eleven sons and a daughter—laying the familial foundations of the tribes of Israel before beginning the return journey to the Land.

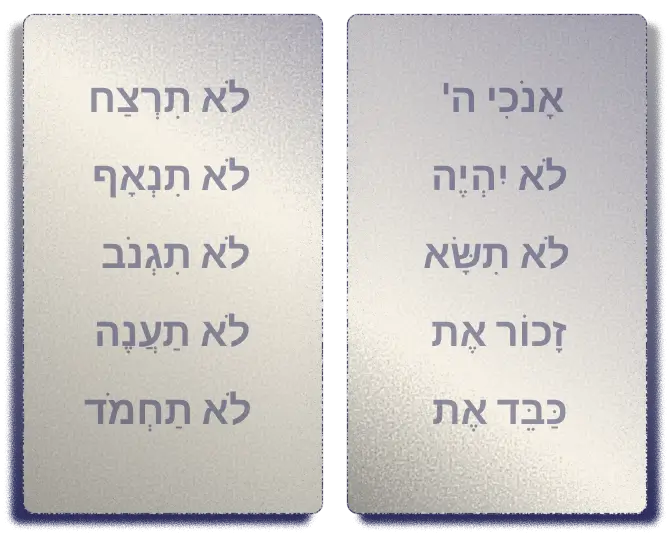

#4 — To love Him — Deuteronomy 6:5

In Vayeitzei: Yaakov’s vision of the ladder at Beit El and Hashem’s promise “I am with you… I will not abandon you” becomes a model of loving Hashem through trust and reliance even in exile; his vow to serve Hashem frames his entire journey as avodah from love, not fear alone.

Narrative roots: Genesis 28:10–22.

#13 — To love other Jews — Leviticus 19:18

In Vayeitzei: Yaakov’s deep love for Rochel, his willingness to serve fourteen years, and his patient care for Leah, Bilhah, and Zilpah illustrate ahavas Yisrael beginning in the home; love of spouse and family is presented as a ladder toward loving every Jew.

Narrative roots: Genesis 29:18–30; 29:31–30:24.

#22 — To learn Torah and teach it — Deuteronomy 6:7

In Vayeitzei: Chazal describe Yaakov’s fourteen hidden years in the beis midrash of Shem and Ever before he sets out; his encounter with “the place” (Beit El) becomes a makom Torah and tefillah that will later be a model for his children.

Narrative roots: Genesis 28:10–11 (with Midrashic backdrop).

#77 — To serve the Almighty with prayer daily — Exodus 23:25

In Vayeitzei: Yaakov’s tefillah at Beit El and his ongoing cries during years of hardship with Lavan show a life of constant prayer; Rachel and Leah, in the naming of their sons, turn every joy and pain into direct speech to Hashem.

Narrative roots: Genesis 28:20–22; 29:31–35; 30:6–24.

#122 — To marry a wife by the means prescribed in the Torah (kiddushin) — Deuteronomy 24:1

In Vayeitzei: Yitzchak commands Yaakov to take a wife from Avraham’s family, and Yaakov secures his marriages to Leah and Rochel through formal agreements and years of avodah in place of kesef—highlighting that building a bayis ne’eman is through covenantal marriage, not casual relationships.

Narrative roots: Genesis 28:1–5; 29:18–30.

#124 — Not to withhold food, clothing, and marital intimacy from one’s wife — Exodus 21:10

In Vayeitzei: Despite Lavan’s exploitation, Yaakov shoulders exhausting shepherding labor “by day the heat consumed me and frost by night” to provide fully for his wives and children, embodying the husband’s obligation to sustain and care for his family.

Narrative roots: Genesis 29:20; 30:25–43; 31:38–42.

#125 — To have children with one’s wife — Genesis 1:28

In Vayeitzei: The parsha is the birth-story of Klal Yisrael, as Yaakov fathers eleven shevatim and Dinah; the yearning of Rachel and Leah for children and their willingness to sacrifice for that future underscore pru u’rvu as a covenantal mission, not only a personal desire.

Narrative roots: Genesis 29:31–30:24.

#162 — Not to marry non-Jews — Deuteronomy 7:3

In Vayeitzei: Yitzchak explicitly warns Yaakov “Do not take a wife from the daughters of Canaan,” sending him instead to the family of Avraham; Yaakov’s willingness to leave home and endure exile in Charan to avoid intermarriage becomes the archetype for guarding the sanctity of Jewish marriage.

Narrative roots: Genesis 28:1–5.

#214 — To fulfill what was uttered and to do what was avowed — Deuteronomy 23:24

In Vayeitzei: Standing at Beit El, Yaakov vows that if Hashem guards him, he will dedicate his life, his home, and a tenth of his possessions back to Hashem; his later return to Beit El (in Vayishlach) and ongoing avodas Hashem flow from this neder, modeling the seriousness of keeping one’s word.

Narrative roots: Genesis 28:20–22 (with fulfillment hinted in 35:1–7).

#475 — Not to withhold wages or fail to repay a debt — Leviticus 19:13

In Vayeitzei: Lavan repeatedly changes Yaakov’s wages and withholds what is due, serving as the negative foil; Yaakov’s outrage at this injustice and his own meticulous honesty with the flock highlight the Torah’s demand not to cheat workers or delay their pay.

Narrative roots: Genesis 29:15–30; 30:25–36; 31:6–9, 38–42.

#499 — Buy and sell according to Torah law — Leviticus 25:14

In Vayeitzei: The complex wage agreements over speckled and spotted sheep, and the later covenant sworn between Yaakov and Lavan, provide an early template for transparent business terms, honest accounting, and the avoidance of ona’ah (wronging one another in commerce).

Narrative roots: Genesis 30:25–43; 31:44–54.

#501 — Not to insult or harm anybody with words — Leviticus 25:17

In Vayeitzei: Lavan’s harsh accusations against Yaakov—“What have you done, deceiving me and carrying off my daughters like captives of the sword?”—contrast with Yaakov’s restrained, dignified response, underscoring how the Torah forbids verbal abuse even amid conflict.

Narrative roots: Genesis 31:26–30, 36–42.

#584 — Respect your father and mother — Exodus 20:12

In Vayeitzei: Yaakov accepts exile to Charan because his parents instruct him to flee Esav and seek a proper shidduch; his departure with their blessing and his ongoing concern for returning home safely reflect kibbud av va’eim expressed through life decisions, not only daily gestures.

Narrative roots: Genesis 28:1–7; 31:3; 31:13; 31:38; 32:1–3.

Rashi reads Vayeitzei as the story of a tzaddik leaving the intense sanctity of his parents’ home and carrying that sanctity into exile, with Beit El / Har HaMoriah functioning as the spiritual hinge between the two worlds.

The parsha opens, “Vayeitzei Yaakov mi’Be’er Sheva – And Yaakov went out from Be’er Sheva” (28:10). Rashi notes that the verse could have simply said “vayeilech Yaakov Charana – and Yaakov went to Charan,” yet the Torah highlights his departure to teach that when a tzaddik leaves a place, he takes with him its hod, ziv, hadar – its glory, radiance, and beauty. The city feels the loss of his presence.

On the road, Yaakov “encounters the place” – vayifga bamakom (28:11). Rashi identifies “the place” with Har HaMoriah, the future site of the Beit HaMikdash, already called hamakom in the Akedah narrative. This is not a random stop but a return to the locus of Avraham’s and Yitzchak’s prayer.

The verb vayifga itself, Rashi explains, also bears the sense of prayer, learning from “אַל תִּפְגַּע בִּי” in Yirmiyahu. From here Chazal derive that Yaakov instituted the evening prayer (Ma’ariv). At the same time, the Torah avoids the usual vayitpallel, instead using vayifga, to hint that the earth “contracted” for him – kefitzat ha-derech – so that the Makom of the Mikdash would come toward him and meet him.

Rashi further deepens the symbolism of the dream: the ladder’s foot is in Be’er Sheva, its top in Beit El, and the center of its incline aligned with Yerushalayim. It images the axis connecting Yaakov’s current flight from home, the future Mikdash, and the broader geography of Eretz Yisrael. The angels ascending are those of Eretz Yisrael returning heavenward; the ones descending are the angels appointed to accompany him in exile. Yaakov’s personal journey thus becomes the template for Divine providence in and out of the Land.

Ha-Shem’s promise, “Ani Hashem… ve’Elokei Yitzchak” (28:13), is, for Rashi, not just comfort but a precise covenantal statement: the blessing to Avraham’s seed is being transferred specifically through Yaakov and not Esav, as implied by the earlier phrase “ki b’Yitzchak” – “in” Isaac, but not all of Isaac’s progeny. At the same time, Rashi notes that G-d unusually links His Name with a tzaddik while still alive (Elokei Yitzchak), because Yitzchak’s physical state – blind and house-bound – renders him like one already removed from the domain of the yetzer hara.

Yaakov’s vow in response (28:20–22) is not conditional bargaining but, in Rashi’s reading, a structured acceptance of each element of Ha-Shem’s promise. “If G-d will be with me… will guard me… will give me bread to eat… and I return b’shalom” – Rashi ties each phrase explicitly back to “ve’hinei Anochi imach,” “ushmarticha,” and “ki lo e’ezavcha” of verse 15, while interpreting shalom as spiritual integrity – returning from Lavan untainted by his ways. The closing “Hashem yihyeh li le’Elokim” becomes a prayer that G-d’s Name rest upon him and his descendants without blemish, fulfilling the promise first given to Avraham.

Within this frame, Rashi’s later comments in the Lavan narratives (chapters 29–31) highlight Yaakov’s moral steadfastness in exile: his honest and exhausting shepherding, despite Lavan’s repeated wage-changes; his scrupulous refusal to benefit from torn or stolen animals; and the miraculous manipulations that ensure his survival and growth are from Ha-Shem rather than trickery. Yaakov thus embodies the “departed tzaddik” whose presence brings blessing even to a Lavan, and whose return to the Land is prepared from the very moment he stepped out of Be’er Sheva.

📖 Source

For Ramban, Parshas Vayeitzei is not merely a narrative of Yaakov’s flight, marriages, and growing family, but a foundational text about the Beis HaMikdash, the structure of Divine providence, and the long arc of Jewish history in exile. Yaakov’s dream of the ladder becomes a metaphysical vision of how the world operates—malachim ascending to receive Divine command and descending to execute it—while simultaneously affirming that Yaakov and his descendants live under a higher tier of hashgachah, directly guided by Hashem rather than by intermediaries. Ramban also reads in the ladder the future rise and fall of the four empires that will dominate Israel, culminating in the eventual collapse of Edom. The parsha’s geography likewise becomes symbolic: the interplay of Be’er Sheva, Beis El, and Har HaMoriah maps the spiritual topography of prayer, with the Mikdash emerging as the “gate of heaven” through which all tefillos ascend.

Yaakov’s neder upon awakening expresses his commitment to serve Hashem fully upon returning to Eretz Yisrael, grounding Ramban’s sharp assertion that true covenantal relationship thrives in the Land. Likewise, the scenes with the well and flocks become a mashal for the Beis HaMikdash and the three pilgrimage festivals, in which Israel gathers to receive blessing as water from a spring. The complex family dynamics between Rachel, Leah, and the shevatim reflect the prophetic process of building Beis Yisrael. The episode of Yaakov’s unusual breeding strategies highlights Ramban’s theology of hishtadlus versus Divine intervention—Hashem guides the outcome despite Lavan’s manipulations, as symbolized by Yaakov’s dream of the patterned rams.

Contrasted with Yaakov’s reliance on hashgachah is Lavan’s dependence on teraphim, which Ramban identifies as occult divination tools rather than genuine deities—devices Rachel removes to break her father’s idolatrous habits. The covenant at Gal’ed/Mitzpah underscores Hashem’s protection over Yaakov’s Divinely mandated journey. The parsha closes with Mahanaim, a revelation of angelic guardianship that frames the narrative’s central contrast: human attempts to manipulate fate through superstition versus the authentic Divine providence symbolized in Yaakov’s visions.

📖 Source

For Rambam, Vayeitzei is not primarily about miracles or family drama. It is a chapter in the education of a future am Hashem: how a human being rises toward truth through ordered knowledge, disciplined character, and structured avodah.

At Beit El, Yaakov’s dream discloses the metaphysical architecture that Rambam sketches in Moreh Nevuchim. The ladder “set on the earth and its head in the heavens” represents the graded chain of being, with the “angels” as the incorporeal forces through which Hashem governs the world (Moreh II:6, II:10). They “ascend” and “descend” as they receive and execute Divine command, but above the entire system stands Hashem alone. The dream corrects any hint of dualism or astrological determinism: there is one simple, transcendent First Cause (Moreh I:49–50), and everything that occurs below flows from His will, mediated but not rivaled by the celestial order.

Prophecy, in this vision, is not entertainment or escape but education. Yaakov is shown not random wonders but the intellectual form of truth—how creation is structured and how providence works. In Moreh III:17–18, Rambam teaches that hashgachah pratit intensifies in proportion to a person’s knowledge of Hashem and moral refinement. Vayeitzei illustrates this principle: Yaakov’s unwavering honesty in Lavan’s house—his refusal to steal, to falsify wages, or to relax his standards when no one is watching—aligns him with the Divine intellect that orders the world. His protection is not arbitrary favoritism; it is the natural consequence of living in harmony with reality as Hashem made it.

Yaakov’s response at Beit El is paradigmatically “Rambamian.” Confronted with awe, he does not remain in ecstasy; he makes a neder. “This stone… shall become a house of Elokim, and of all that You give me I will surely tithe.” For Rambam, this is precisely what genuine religious experience must produce: mitzvot that channel emotion into law and ongoing service (Moreh III:32; Hilchot Nedarim 1:1). The encounter yields structure—place, practice, and commitment—rather than wandering spirituality.

The years in Charan then become a laboratory for Rambam’s ethics. In Hilchot De’ot 1–2, he describes character perfection as the balanced “middle way,” acquired through repeated, intentional actions. Yaakov’s life with Lavan—work at all hours, patience under exploitation, measured speech, refusal to live by resentment—forms exactly this steady shaping of the middot. He does not escape the material world; he disciplines it. In Rambam’s language of Hilchot Teshuvah 9:1, the true reward for this path is not wealth (though Yaakov receives that too) but deveikut—closeness to Hashem.

Finally, Rambam’s broader theology of Eretz Yisrael hovers in the background. Yaakov’s promise to return and build a “house of Elokim” fits Rambam’s insistence that holiness is most fully realized in the Land, where prophecy and national service are meant to flourish (Melachim 11:12). Exile, then, is a corridor: not a denial of holiness but a preparation for its higher form. Yaakov leaves Be’er Sheva as a lone fugitive and returns as a person whose mind, deeds, and commitments have been educated into alignment with the One.

In Rambam’s reading, Vayeitzei becomes the story of how a human being turns vision into order: from dream to doctrine, from awe to obligation, from wandering fear to a life of disciplined closeness to Hashem.

Key Rambam Themes in Vayeitzei

📖 Sources

Moreh Nevuchim

Mishneh Torah

For Ralbag, Yaakov’s dream in Vayeitzei is not a mystical escape but a philosophical diagram of reality. The ladder “set on the earth and its head in the heavens” represents the entire ordered structure of existence, step by step, from the lowest forms up through the separate intellects, all ultimately dependent on one single First Cause, Hashem (Ralbag to Bereishit 28:10, To‘alot 5, 11). Against dualist theories, Ralbag insists there is One source for both the sublunar world of change and the celestial spheres.

Prophecy, in this reading, is Hashem revealing the true architecture of the world and the pattern of hashgachah. Yaakov is shown that specific, continuous providence over an individual is possible only from Hashem, not from “the system” alone (To‘alot 7). Divine care is more than material protection; it includes being granted true beliefs and right opinions, which Ralbag calls a higher form of hashgachah (To‘alot 8).

Yaakov’s vow at Beit El then becomes a philosophical response: if reality is structured toward the One, human life must be structured in return — through avodah, ma’aser, and a dedicated makom of service — to align with that unity (Ralbag ad loc.).

📖 Sources

Vayeitzei — Exile, Encounter, and the Birth of Inner Avodah

Vayeitzei marks Yaakov’s first step into exile — both geographic and spiritual. Chassidic masters see this journey not merely as escape from Esav, but as the soul’s descent into the complexity of the world: a movement from sheltered holiness into the disorder of life, where avodah becomes real. In this parsha, Yaakov discovers that holiness is not confined to the Beit Midrash but emerges precisely within the confusion, labor, and emotional entanglements of living.

The Baal Shem Tov teaches that Yaakov’s dream reveals the secret of spiritual ascent: angels “ascending and descending” reflect the rhythm of inner life — moments of rise, moments of fall. The ladder is the soul’s journey: one must begin “מוצב ארצה,” firmly grounded, for the ascent toward heaven to endure. The vision affirms that even our lowest places contain the possibility of connection.

The Kedushat Levi explains that Yaakov’s vow — “bread to eat and clothing to wear” — expresses the ideal of kedushat ha-gashmiyut: transforming basic physical life into a vessel for holiness. Naming the site Beit El signifies that even ordinary space can become a “house of G-d” when infused with intention.

The Sfas Emes (Vayeitzei 5631–5633) teaches that Yaakov’s years with Lavan model the deepest refinement: serving with integrity in a place of deception. Yaakov’s work becomes a template for avodat ha-berurim, uplifting sparks hidden within difficult relationships and mundane labor. His struggle is the soul’s struggle — to remain aligned while surrounded by distraction.

In Vayeitzei, the Chassidic vision reveals exile as opportunity: the ladder rises from the lowest ground, routine becomes revelation, and the journey itself becomes the birthplace of holiness.

📖 Sources

In Vayeitzei, Yaakov's journey outward becomes a journey inward. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks reads this parsha as the moment the future Israel learns to find holiness not in sanctuary or stability, but in uncertainty, exile, and moral responsibility.

Through Rabbi Sacks’s lens, Vayeitzei becomes the story of the first Jewish exile but also the birthplace of Jewish hope. Holiness rises from the lowest ground; prayer becomes a ladder; unseen tears are gathered by Heaven; and justice and love together create the world we long for.

📖 Sources

Rav Kook reads Vayeitzei as a parsha of spiritual ascent within exile, where Yaakov learns to uncover Divine light in foreign lands, in difficult relationships, and in the quiet depths of the soul. Across these teachings, Rav Kook traces how prayer, struggle, learning, and destiny converge to form Israel’s unique path: a people capable of sanctifying the present while carrying the burden of the future.

1. The Ladder and the Structure of the Soul

In “The Prayers of the Avot,” Rav Kook teaches that Yaakov's ladder reflects the multi-layered nature of prayer and the human soul. Avraham embodies morning prayer (renewal), Yitzchak the afternoon prayer (continuity), and Yaakov the evening prayer (faith in darkness). Yaakov's dream reveals that the soul can ascend even when circumstances descend. His encounter with the ladder inaugurates the Jewish capacity to meet Hashem not only in clarity, but in confusion — to transform exile into connection. The angels ascending first symbolize that our efforts below awaken Divine response above, a foundational principle of spiritual growth.

2. Prayer Before Sleep: Faith Amid Uncertainty

Rav Kook connects Yaakov's nighttime prayer to Kriat Shema al haMitah. Just as Yaakov lay down in fear and exile, a person prepares for sleep by entrusting the soul to Hashem despite uncertainty. Night symbolizes a world where understanding is dimmed and the future is hidden; yet precisely there, a higher faith awakens. Yaakov teaches that spiritual resilience is forged not only in daylight clarity but in the courage to rest, release control, and believe that the soul will rise renewed. Sleep becomes an act of emunah — a nightly rehearsal of trust.

3. The Transformative Presence of Torah

In “The Blessing of a Scholar’s Presence,” Rav Kook explains that a true Torah scholar radiates inner light that uplifts the spaces and people around him. Yaakov's arrival at Lavan’s home subtly changes the moral and spiritual atmosphere; even Lavan acknowledges that blessing has entered with him. For Rav Kook, this reflects a broader principle: holiness is not withdrawal but influence. By carrying elevated consciousness into ordinary life — the workplace, the home, the field — one infuses reality with growth. Israel’s mission begins with Yaakov's ability to sanctify even the most spiritually compromised environment.

4. Rachel and Leah: Present Beauty and Hidden Future

Rav Kook interprets the rivalry between Rachel and Leah as a metaphysical tension between the revealed present and the concealed future. Rachel represents the world as it appears — beauty, clarity, emotional immediacy. Leah represents destiny, the deeper spiritual future that is not always visible in the moment. Yaakov naturally loves Rachel, but the future of Israel — leadership, priesthood, kingship — is destined to emerge from Leah.

This duality shapes Jewish history: Yoseph vs. his brothers, Saul vs. David, and ultimately Mashiach ben Yosef vs. Mashiach ben David. Rav Kook teaches that Israel must learn to honor both dimensions — to elevate the present through truth and integrity, while also embracing the hidden, often disruptive future that pushes the world toward redemption. In Vayeitzei, Yaakov discovers that holiness often arrives disguised, projecting the future into the imperfect present so that it may be elevated.

Together, these teachings reveal Rav Kook’s vision: prayer deepens the soul, uncertainty refines trust, Torah elevates the everyday, and destiny unfolds through hidden paths. Yaakov's exile becomes the birthplace of Israel’s unique spiritual resilience — the ability to uncover light in the very places that seem furthest from it.

📖 Sources

The parsha of Vayeitzei speaks across generations because it explores a universal human experience: learning to carry holiness into places that feel foreign, demanding, or unclear. Yaakov leaves the sanctity of his parents’ home and discovers that spiritual life does not wait for ideal conditions. It must be lived in exile, in workplaces, in complicated relationships, and in long, quiet years of effort. The commentaries show how Vayeitzei becomes a guide for modern spiritual resilience.

1. Holiness in Unlikely Places

Rashi and Ramban teach that Yaakov’s “encounter with the place” reveals that sacred moments often arise unexpectedly. The ladder standing between earth and heaven shows that even imperfect ground can become a gateway of connection. The message for today is simple but radical: transformation is possible anywhere. A person does not need ideal settings to grow. In confusion, travel, transition, or isolation, one can still turn to Hashem and find new openings for tefillah and awareness.

2. Integrity When No One Is Watching

Yaakov’s decades in Lavan’s household model moral clarity in morally ambiguous environments. Ramban highlights his honesty in labor, his refusal to cut corners, and his steadfastness despite exploitation. Rambam deepens this: providence attaches itself to minds and characters aligned with truth. The modern world often rewards cleverness over character; Vayeitzei argues that real success—spiritual and even material—flows from disciplined integrity, not manipulation.

3. Faith Through Uncertainty and Darkness

From Rashi’s Ma’ariv to Rav Kook’s teaching on Kriat Shema al haMitah, Vayeitzei is a parsha of nighttime faith. Yaakov rests on stones, unsure of the future, yet places his trust in Hashem. Rav Kook views this as the essence of spiritual maturity: the courage to move forward even when clarity is absent. In a world saturated with fear and constant information, Vayeitzei urges calm trust, quiet resolve, and the steady practice of returning the soul to Hashem each day and night.

4. Building the Future One Honest Step at a Time

Ramban, Ralbag, and the Chassidic masters converge on a theme: growth is incremental. Yaakov’s dream may reveal cosmic order, but his life unfolds in small acts—moving stones, tending sheep, raising a family. Ralbag emphasizes that Divine wisdom becomes real only when it structures daily life; the Chassidic sources highlight avodat ha-berurim, refining sparks through work, relationships, and mundane responsibilities. Today’s culture celebrates instant results and sweeping change. Vayeitzei teaches that futures are built through quiet perseverance.

5. Seeing Hidden Pain, Honoring Hidden Strength

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks and Rav Kook both focus on Leah. Her tears, unnoticed by others, shape the destiny of Israel. Modern life often overlooks silent suffering and undervalues the inward, unseen work of spiritual refinement. Vayeitzei calls us to deeper compassion: to notice the unspoken pain around us, to honor the Leah-like strength hidden beneath the surface, and to recognize that many of history’s greatest blessings begin in moments of heartbreak.

6. The Eternal Struggle Between Present Comfort and Future Vision

Rav Kook’s reading of Rachel and Leah presents a tension between the beautiful present and the challenging demands of the future. Life requires both: the ability to appreciate what is visible and the courage to commit to what is not yet seen. Careers, relationships, community-building, and spiritual growth all demand the balance between present joy and long-term purpose. Vayeitzei guides us to embrace both—cherishing today while remaining faithful to a higher trajectory.

7. Prayer as Ascent, Work as Worship

The ladder symbolizes an integrated spiritual life: prayer that reaches upward and action that descends into the world. Rambam emphasizes that true religious experience becomes law, structure, and obligation; Rav Kook adds that Torah consciousness elevates even the most ordinary tasks. Vayeitzei encourages us to see our routines—work, family, effort—not as detours from holiness but as the very stages where spiritual ascent is forged.

In daily life, Vayeitzei calls us to become like Yaakov:

to hold fast to truth in environments that challenge it,

to seek holiness in unpolished places,

to persevere through darkness with trust,

to notice the vulnerable and honor the hidden future,

and to build a life where prayer and action, heaven and earth, meet on our personal ladders.

Rashi: Why mention “going out”?

Conceptual theme: Beginning of exile; absence of holiness

This Rashi frames the entire parsha as the exile of holiness from place:

a. “Vayifga bamakom” – Which “place”?

b. “Vayifga” = Tefillah (Maariv)

Thematic layer – Tefillah + Beit HaMikdash:

c. “Ki va hashemesh” – Sun setting early

d. Stones around his head

Conceptual read: unity around the head of Israel

e. “Vayishkav bamakom hahu” – He slept there

a. “Sulam… olim veyordim” – angels up first, then down

b. “Hashem nitzav alav” – G-d stands “over him”

c. “Elokei Avraham… veElokei Yitzchak”

Theme – Generational Covenant:

d. “Ha’aretz asher ata shochev aleha” – collapsing the entire Land

e. Promise of descendants and universal blessing (28:14)

f. 28:15 – Four-fold promise mapped into Yaakov’s later neder

Hashem says:

Rashi ties “dibarti lach” back to Avraham: all the promises to Avraham’s “seed” are now concretely designated for Yaakov, not Esav (“ki b’Yitzchak – velo kol Yitzchak”).

Conceptual theme: Exile, Protection, and Election

a. “Achen yesh Hashem bamakom hazeh… va’anochi lo yadati”

b. “Mah nora hamakom hazeh” – “Nora” as an ontological category

c. “Ein zeh ki im Beit Elokim, v’zeh Sha’ar HaShamayim”

Big theme – Prayer and Mikdash as Axis Mundi

d. Movement of Har HaMoriah – “Kefitzat Ha’aretz” re-read

Yaakov’s conditions:

Rashi systematically maps each phrase back to the Divine promise of v.15:

Key conceptual points:

So: the entire dream + neder package = “theology of exile”

At this point we’ve set the theological backbone of the parsha: exile under Providence, Mikdash as axis, tefillah as response. The rest of Vayeitzei plays out those themes largely through family and economic life.

Below I’ll move a little faster through the later sections, still showing how Rashi’s comments map into bigger ideas.

29:1–14 – The Well, Rachel, and Lavan

29:15–30 – Wages, Deception, and Two Sisters

Key Rashi notes:

Themes:

29:31–30:24 – Births and Names as Theological Commentary

Rashi uses each child’s name as a window into:

Big thematic wrap:

Theme:

Leaving Lavan (31:1–21)

The confrontation and treaty (31:22–55)

Rashi here turns the narrative into a meditation on:

32:1–3 – Return to Angels, Return to Land

The parsha closes where it began:

📖 Source

For Ramban, Vayeitzei is not just the story of Yaakov running from Eisav and building a family. It is a parsha about the Beis HaMikdash, the future of Klal Yisrael, and how Hashem’s hashgachah works in exile.

When Yaakov sees the ladder “set on the earth and its top reaching the heavens,” Ramban explains that Hashem is revealing two intertwined ideas (Ramban to 28:12):

Ramban then brings the Midrash that this ladder also showed Yaakov the four future empires that would dominate Jewish history – Bavel, Madai, Yavan, and Edom – each “ascending” in power, and then falling. Only Edom seems to keep climbing without coming down… until Yaakov declares: “Yet you will be brought down to She’ol.” Hashem answers: however high Edom tries to soar, it will eventually fall.

So in one image, Yaakov is shown:

Ramban spends a lot of energy clarifying where Yaakov actually is when he dreams, and what is happening with Be’er Sheva, Beis El, and Har HaMoriah (Ramban to 28:17).

He brings Chazal that call this place “Beis El” and identify it with the Mikdash, “the gate of heaven” through which tefillos and korbanos rise. But the pesukim also talk about Luz, Be’er Sheva, and Har HaMoriah. Ramban maps the Midrashim carefully:

Ramban rejects the idea that Har HaMoriah was physically uprooted and moved to Beis El; instead, he reads the “springing of the earth” as a miraculous shortening of distance – the way Eliezer reached Charan “in one day.” The earth “jumps” for Yaakov multiple times, so he can reach all these holy points quickly.

The takeaway for Ramban:

Vayeitzei thus becomes a parsha about where prayer reaches heaven and how Yaakov’s journey “establishes” those places as holy.

When Yaakov vows, “If Elokim will be with me… then Hashem will be my G-d,” Ramban is bothered: is Yaakov making his avodas Hashem conditional (Ramban to 28:20–21)?

He explains:

Ramban then adds a sharp line:

Chazal say, “Whoever lives outside Eretz Yisrael is like one who has no G-d.” Yaakov is promising that when he returns to the Land, his relationship with Hashem will take on its full covenantal form.

So Yaakov’s neder is not a bargain, but a commitment to bring his avodah back into the Land, centered on the future Mikdash.

The long story of Yaakov arriving at the well, moving the stone, and watering Rachel’s flock is not just romantic narrative. Ramban sees a mashal for the Mikdash and aliyah la’regel (Ramban to 29:2):

Through the Mikdash, “Torah goes forth from Tziyon” like water from a spring, and Israel draws ruach hakodesh and blessing from those visits. Then the “stone” is set back until the next festival.

For Ramban, the story is quietly saying: Yaakov’s mission in exile is already ordered toward a future Mikdash and the rhythm of national avodah.

Ramban reads the tensions between Rachel and Leah not as petty rivalry, but as the painful process of building the twelve shevatim.

Leah’s naming of her children is also theology:

Even the duda’im episode becomes layered: Ramban holds that Rachel wanted them for pleasant fragrance, possibly for Yaakov’s couch, a way to win back time and affection. Under that very human gesture is the slow, unfolding reshaping of the bayis that will become Israel.

Ramban’s treatment of the speckled, spotted, and brown sheep is one of the classical places where he ties nature, segulos, and hashgachah together (Ramban to 30:32–43):

Yaakov may do his hishtadlus, but the actual wealth-building is from Hashem’s providence responding to Lavan’s injustice. Vayeitzei becomes a case study in how a tzaddik works honestly, uses seichel, but ultimately attributes success to Hashem.

Ramban’s analysis of Lavan’s teraphim is subtle (Ramban to 31:19):

Rachel steals them, says Ramban, to wean her father from avodah zarah and from dependence on these devices. Lavan’s fury—“Why did you steal my gods?”—exposes how deep that dependence is.

Later, when Lavan proposes the stone-pile covenant at Galed/Mitzpah (31:44–49), Ramban explains:

Finally, the parsha closes with Mahanaim – “the camp of angels” (32:2). Ramban argues that Yaakov is still outside Eretz Yisrael; this vision appears because he’s entering dangerous territory, moving toward Esav. The message: there is another camp, invisible but real, surrounding him.

Together, the end of Vayeitzei frames a contrast:

📖 Source

For Sforno, Vayeitzei is the blueprint of Jewish exile: Yaakov is forced from home, descends into a world of trickery and uncertainty, yet carries with him a promise that Am Yisrael will never be abandoned. The parsha traces three interwoven themes—future redemption, the unique holiness of Eretz Yisrael, and the ethical way a Jew is meant to live even in the house of Lavan.

Yaakov does not plan to reach the holy site; he “happens upon” a simple travelers’ inn. Only later does he realize that this makom is a prophetic gateway. Sforno reads the dream as a vision of history:

When Yaakov awakens and exclaims, “Surely Hashem is in this place,” Sforno emphasizes that he has stumbled into a site naturally fit for prophecy—Eretz Yisrael’s air itself refines and makes one wise. The ladder teaches that the Beit HaMikdash will be the “gate of heaven,” where prayers ascend most directly.

Yaakov responds with a neder that, in Sforno’s reading, is strikingly modest:

For Sforno, Yaakov’s vow is not conditional bargaining, but a commitment to live under din. Once redeemed, Hashem will not merely “not abandon” Israel; He will “walk among them” in an elevated, continuous relationship.

Sforno reads the Lavan episodes as a sustained portrait of tzidkut under pressure:

For Sforno, this entire section teaches that the Avot related to intimacy as Adam and Chava were meant to before the sin: not for self-indulgence, but to raise souls who would serve Hashem.

When Yaakov asks to return home, Sforno insists he already had enough means to support his family; he would never rely on miracles for basic survival. Lavan, aware that blessing followed Yaakov, begs him to stay.

In the wage-negotiation and speckled-sheep episode, Sforno balances nature and providence:

Yaakov’s line “Hashem has blessed you at my feet” is accepted as true: a Torah scholar’s presence brings berachah. Yet Sforno underlines Yaakov’s professional excellence—he heals wounded animals, prevents miscarriages, and refuses even what other shepherds might take as their due.

Once Lavan’s sons slander Yaakov and Lavan’s face changes, Hashem commands Yaakov to return home. Sforno explains Yaakov’s “theft of Lavan’s heart” and silent flight not as cowardice but as self-defense: remaining would likely mean financial and physical ruin.

The covenant at Gal-Ed and Mitzpah is read as a mutual non-aggression pact. Lavan insists on pairing “the god of Nachor” with “the G-d of Avraham,” but Yaakov swears only “by the Fear of his father Yitzchak,” signaling his exclusive loyalty to the G-d of Israel.

Finally, as Yaakov departs, Sforno notes two blessings:

For Sforno, this is the goal of Vayeitzei: to show that exile, when lived with integrity, hishtadlut, and tefillah, transforms a vulnerable wanderer into a “machaneh Elokim” — a living testimony that Hashem guards His people through all the rises and falls of history.

📖 Source

Abarbanel begins by re-structuring the parsha into three thematic units:

The global kavvanah: to show that in Yaakov’s going out, his stay in Charan, and his return, Hashgachah Elokit “accompanied him continually; Hashem was with him, never abandoning nor forsaking him.” Everything — ladder dream, marriages, children, wealth, and escape — is governed by providence, not accident.

Abarbanel first raises a series of questions on this opening scene, including:

Answer: triple providence, triple Mikdash

On the peshat level, the triple “makom” signals three providential “coincidences”:

All of this is orchestrated from Above to stage the dream.

On the deeper level, the three “makom” allude to the three future Batei Mikdash on this site:

Thus, Yaakov’s personal stop at “hamakom” becomes a prototype for his descendants’ relationship with the Mikdash — “ma’aseh avot siman lebanim.”

Abarbanel carefully lays out seven major interpretations of the ladder (Rashi/Chazal, R. Eliezer HaGadol, Ibn Ezra’s “neshamah,” Ramban’s Malachim/run-the-world model, Rambam’s various readings in Moreh, etc.), and then critiques them:

Abarbanel’s own peshat: Mikdash + Validation of the Berachot

He therefore proposes a reading tied directly to Yaakov’s crisis:

The dream thus reassures Yaakov on three fronts: his past (berachot not a sin), his present (protection from Esav and Lavan), and his future (land, seed, Mikdash, and national destiny).

Abarbanel raises a cluster of difficult questions:

Resolving the doubts:

Thus Abarbanel answers the theological difficulty: Yaakov is not a conditional opportunist; he is a novice navi seeking confirmation that his dream is true nevu’ah and that sin will not block its fulfillment.

Abarbanel devotes a full question (Q7) to the seemingly trivial story of shepherds, a heavy stone, and three flocks. What is the Torah teaching?

He offers multiple layers:

In all of this, Abarbanel emphasizes that the narrative is not folkloric filler: it is a symbolic overture to the themes of marriage, fertility, and the future Mikdash.

Several of Abarbanel’s most striking questions concern Yaakov’s marital choices:

Abarbanel’s multi-layered answer:

Abarbanel’s analysis of the naming of the shevatim is very psychological and tightly question-driven:

His resolution:

Abarbanel addresses the dudaim episode and its seeming triviality.

His answer:

Abarbanel devotes one of his longest question-sets to Yaakov’s partnership with Lavan and the striped-stick strategy:

Core points:

Abarbanel’s last block treats the exit narrative and raises many sharp questions (Q1–Q16 on this section), among them:

Key resolutions:

The parsha closes with machanayim: as soon as Yaakov separates from Lavan and his legal struggle ends, he is once again greeted by Mal’achei Elokim, returning him to the prophetic atmosphere of the ladder. The personal story of exile has now fully circled back to the covenantal story of Israel’s destiny.

📖 Source

Hachanah, Ahavah, and the Ladder of Tests

For Rav Avigdor Miller, Vayeitzei is not only the story of Yaakov leaving home and building the future Shevatim. It is a master-class in how a Jew builds an inner world: through preparation, love, and a lifetime of tests that Hashem custom-designs for our perfection.

Vayeitzei opens with a deceptively simple verse:

“Vayeitzei Yaakov miBe’er Sheva va’yeilech Charanah” –

“Yaakov left Be’er Sheva and went to Charan.”

Chazal note that this “short trip” took fourteen years. Yaakov detours into the Beis Midrash of Shem and Eiver, hiding there and learning day and night without lying down to sleep. When his parents said “go marry,” he “learned” that their command included hachanah – serious spiritual preparation.

Rav Miller reads this as a paradigm:

Just as “go buy milk” obviously includes “put on your shoes and coat,” so too “go get married” includes “become the kind of person who can carry a Jewish marriage and build a nation.” Yaakov treats his parents’ words like Torah: studied with iyun and mefarshim, unpacking the assumptions hidden inside.

Already here, Rav Miller is setting up three pillars:

The dream of the ladder – with its feet on the ground and its head in heaven, angels ascending and descending – becomes the symbol of Yaakov’s life: an existence rooted in gritty reality but constantly climbing, rung by rung, toward Hashem.

In “A Career of Preparing”, Rav Miller takes Yaakov’s fourteen-year detour and turns it into a sweeping principle:

“Everything in life becomes better with preparation.

A successful life is a career of hachanah.”

He moves from Yaakov’s vast hachanah for marriage to our smallest daily acts:

Shabbos becomes the weekly laboratory of this principle:

The famous Chazal – “Mi she’tarach b’Erev Shabbos yochal b’Shabbos” – is not folk wisdom about cooking; it’s theology: This world is Erev Shabbos; Olam Haba is Shabbos. If you do not prepare, there is nothing to eat.

Underneath it all is a quiet warning:

One can daven, keep Shabbos, do mitzvos – and if there is no preparatory kavanah, much of it may be “nigah l’rik,” toil that never becomes what it could have been.

In “To Love One Jew”, Rav Miller deepens the emotional core of Vayeitzei by confronting a simple textual problem:

If the Avos loved Hashem with a heart so full there was “no room for anything else,” how can the Torah say “Vaye’ehav Yaakov es Rachel,” and “Vaye’ehaveha Yitzchak” about Rivkah? How could Dovid and Yehonasan love one another “more than the love of a man for a woman”?

The answer:

This love is not a competitor to Ahavas Hashem – it is an expression of it.

Practically, Rav Miller insists we stop playing games with “I love everyone” and begin real work:

Marriage is then recast:

Yaakov’s passionate love for Rachel is elevated from romance into program:

The final layer is how greatness is actually forged.

Chazal on the verse “Gam et zeh le’umas zeh asah Elokim” teach that Hashem not only balances nature (snakes vs. mice), but history:

“Bara tzaddikim, u’le’umas zeh bara resha’im.”

Hashem places tzaddikim and resha’im opposite each other.

Hashem doesn’t force anyone to be wicked; free will remains untouched. But He:

Rav Miller paints a striking scene from Chazal (Avodah Zarah 2a):

With that backdrop, Chazal say about Vayeitzei:

“Yavo Lavan v’ya’id al Yaakov.”

Let Lavan come and testify about Yaakov.

This is startling. We would have assumed that Yitzchak, Rivkah, or Shem v’Eiver would be the primary witnesses to Yaakov’s greatness. Rav Miller says: they are his preparatory yeshivos, but the main crucible of his greatness is Beis Lavan.

When Yaakov later says:

“Im Lavan garti… vayehi li shor v’chamor, tzon v’eved v’shifchah”

Chazal decode this as a catalogue of spiritual acquisitions in Lavan’s crucible:

In other words:

All future Jewish history – Yosef, Moshe, David, Mashiach, the entire “Tzon Kodashim” – is “seeded” in the shleimus Yaakov attains specifically through enduring and elevating his relationship with Lavan.

That yields a radical reading of:

“Im Lavan garti v’taryag mitzvot shamarti.”

Not: “I lived with a rasha and despite him, I kept the mitzvos,”

but: “I lived with Lavan and through him I reached taryag.”

To generalize this to us, Rav Miller leans on the opening of Mesillas Yesharim:

“Kol inyanei ha’olam nisyonot hem la’adam.”

All aspects of this world are tests.

The word nisayon is related to “nisa” – to raise up. A test is an elevator, not a trap.

Mashal: A duck on the rotisserie turns over the fire so every side gets cooked; no raw patches remain. Hashem does this to us with:

Each “difficult person” is a lavanish instrument:

The key, says Rav Miller, is emunah:

Then the wicked – or simply difficult – really do “make us great.”

Put together, Rav Miller’s Vayeitzei becomes a single program:

In short, Vayeitzei becomes the parsha of:

In Rav Miller’s spirit, you could present the “takeaway” like this:

Do this, Rav Miller would say, and you’re not just reading about Yaakov Avinu in Vayeitzei; you’re living Vayeitzei – turning your own journey, loves, and Lavans into a ladder whose head reaches toward Shamayim.

📖 Sources

Dive into mitzvos, tefillah, and Torah study—each section curated to help you learn, reflect, and live with intention. New insights are added regularly, creating an evolving space for spiritual growth.

Explore the 613 mitzvos and uncover the meaning behind each one. Discover practical ways to integrate them into your daily life with insights, sources, and guided reflection.

Learn the structure, depth, and spiritual intent behind Jewish prayer. Dive into morning blessings, Shema, Amidah, and more—with tools to enrich your daily connection.

Each week’s parsha offers timeless wisdom and modern relevance. Explore summaries, key themes, and mitzvah connections to deepen your understanding of the Torah cycle.